How much good - or damage - can leadership do?

I believe that leadership can’t do damage – because leadership is, by definition, a positive thing. When we talk about poor leadership, what we really mean is the failure to lead. In other words, it is the absence of leadership that is negative and therefore damaging.

Which means a better question would be – how much good can someone in a management role do by leading well, and how much damage can a manager do by failing to lead?

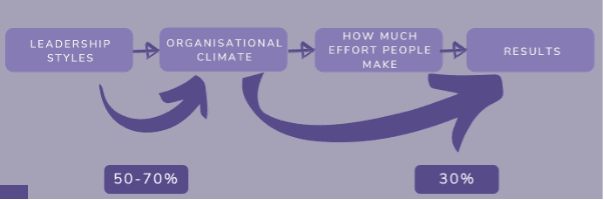

David McLelland https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_McClelland was an American organisational psychologist whose life’s work was on the subject of motivation. He introduced the concept of a leadership chain, which showed the connection between the way leaders lead with the results produced by their teams and organisations.

We will look at a modified version of the leadership chain to those questions. If you want to read about the original chain in detail this is an excellent article.

What the leadership chain demonstrates is that we can work backwards in understanding the performance of individuals and teams:

- How well an individual or team performs is a direct result of how much effort they make. That makes sense – the harder someone tries, the better they perform. Of course, they also need to have some ability, knowledge and resources but none of those things count without effort.

- Let’s work back another step. The amount of effort someone makes is a response to their working climate, which is one part of the broader workplace culture. Again, that makes sense. We have all been that person who didn’t perform at our best because we were in a workplace that sucked the life out of us – and we have all been that person who blossomed in the right environment. McLelland’s research found that we can create a 30% variance (up or down) in performance based on making the working climate better or worse.

- One final step in the chain. Leaders, this is where you come in. The biggest influence on working climate is leadership style. For your team, that is you. Other factors have some influence, but the McLelland research showed that 50-70% of the working climate can be attributed to the leadership style of the immediate leader.

Looking at the chain as whole, if we want to improve results, start with the way people lead. That creates a better working environment which people respond to by making more effort. Improved results are consequence.

We have seen this work in reverse. A good leader moves on and is replaced by a less effective one. Their style impacts the working climate in a negative way, people respond by ‘just coming to work and doing what they have to do, and diminished results are the consequence.

Returning to the original questions, the answer is clearly: A lot! Strong leaders can do a lot of good – by creating environments in which people feel motivated to do their best. Managers who don’t work on their leadership damage team and individual performance because their styles create a demotivating environment.

What would a 30% variance in any key result or metric mean for your team or organisation? A 30% increase or decrease in revenue? Quality? Compliance? Key activity level? Collaboration? Outcome for clients/ patients/ customers? Safety? Innovation?

The crazy part of this is that managers are frequently asked to be leaders without the support and training needed to become leaders. This is a progression we often see – has this happened to you? Does it happen in your organisation?

Most new supervisors and entry level managers are promoted because they are proficient at the task they do, or because they have been with the organisation a long time and are therefore ‘next in line’. We call this the ‘longest and strongest’ approach to leadership selection, and it is based on flawed thinking. They are better at the task than anyone else, or they have been doing it for longer than anyone else, therefore they will be a good leader of the task.

Of course, the truth is that being the ‘longest and strongest’ is a strong foundation for management, but it is a poor basis for leadership – the same leadership that flow through to a variance of 30% in results.

Despite this flawed process, entry level managers and supervisors sometimes seem to be ‘doing OK’. After all, the task continues to be done well. Because their team is usually small, problems like low morale and unresolved interpersonal issues are contained. They aren’t visible outside the team and the new manager manages to ‘keep a lid on them’. They are almost always frustrated by the amount of time they spend dealing with people issues, but they manage them through force of will and by being hands on. Results are not as good as they could be, but we can’t we really expect more from an inexperienced manager, right?

Because the new manager is busy – and with no glaring problems for those outside the team to respond to – they are often left to ‘sink or swim’. If they are provided with training, it is often band aid measures rather than a strategic developmental approach. Other more senior managers are busy dealing with other issues, and don’t have time to provide critical mentoring and on-the-job guidance. People & Culture are dealing with crises, and so the new manager battles on, left to figure things out on their own, unless they have a crisis of their own. And meanwhile, the new manager continues to create that 30% variance, either way, in results.

Then, the flawed logic ramps up. Another, more senior, opportunity opens us. With people hard to recruit, the organisation looks around and sees an emerging manager who is ‘doing OK’, so they promote them. With a move into the more senior role, with more people and more time away from their team – mainly spent in meetings – and more paperwork, cracks start to appear.

With little investment in their development, the manager is left to double down on what they have always done. Their frustration increases, senior leaders start to question whether the right decision has been made, and results continue to be compromised.

Sometimes the conclusion is that there is something wrong with the people in the team. After all, the manager ‘knows their stuff’. Of course, there is some evidence to justify this conclusion – some of the performance and some of the behaviour in the team is not OK. The question we fail to ask is why it is occurring?

We can tell you why. It’s because they have a manager who knows their stuff but a leader who has been left to flounder. The strategies that papered over cracks in a smaller team, where they were hands on, are no longer enough.

The reality is that this is a failure of leadership. Superficially, it looks like the failure of the manager who hasn’t stepped up to leadership. Dig just beneath the surface and we find that it is the failure to help that technical expert develop the leadership capability to sit alongside their managerial and technical prowess. Either way, it’s costing their team and their organisation 30% of whatever metrics matter to them.

The answer isn’t to find someone else and go through the same process. The answer is to provide opportunities to grow as a leader – and have expectations that they will embrace those opportunities. When? Ideally before you need them to move into a role that requires them to be a leader but it’s never too late to help someone grow into a role they already occupy.